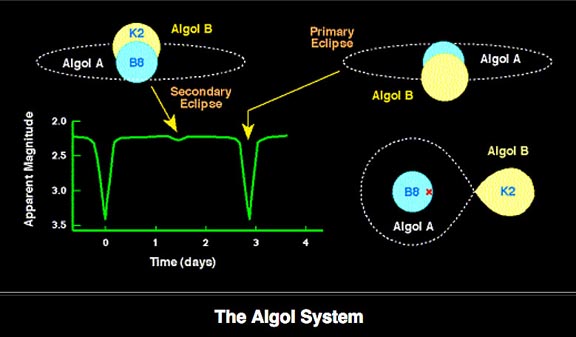

Here's what an eclipse would look like if you could see it up close. The main eclipse (at right) occurs when the larger but dimmer companion star, a K2 orange subgiant, partially eclipses Algol A, a more massive but smaller main sequence star. A small secondary eclipse (left) is observed when the B star passes around the back of the primary. Mike Guidry / Univ. of Tennessee

The dark ways of Algol, the Demon Star, and what it can teach us about stellar evolution.

What if I told you that you could stand in your front yard and watch one star eclipse another 93 light-years away from Earth with nothing but your eyeballs? As improbable as it sounds, this sight is within easy reach of northern hemisphere skywatchers once or twice a month throughout fall and winter.

Algol, nicknamed the Demon Star, resides in the constellation Perseus directly below the “W” of Cassiopeia. The name derives from Arabic “Al-Ghul,” (ghoul) and may hint at its then-mysterious habit of fading away and returning to normal brightness in a matter of hours. We now understand that this evil-spirited behavior can be blamed on Algol B, its dimmer companion star. Every 2.87 days, Algol B partially eclipses the hotter and brighter Algol A. Astronomers refer to this pair as an eclipsing binary.